Gravitational Waves

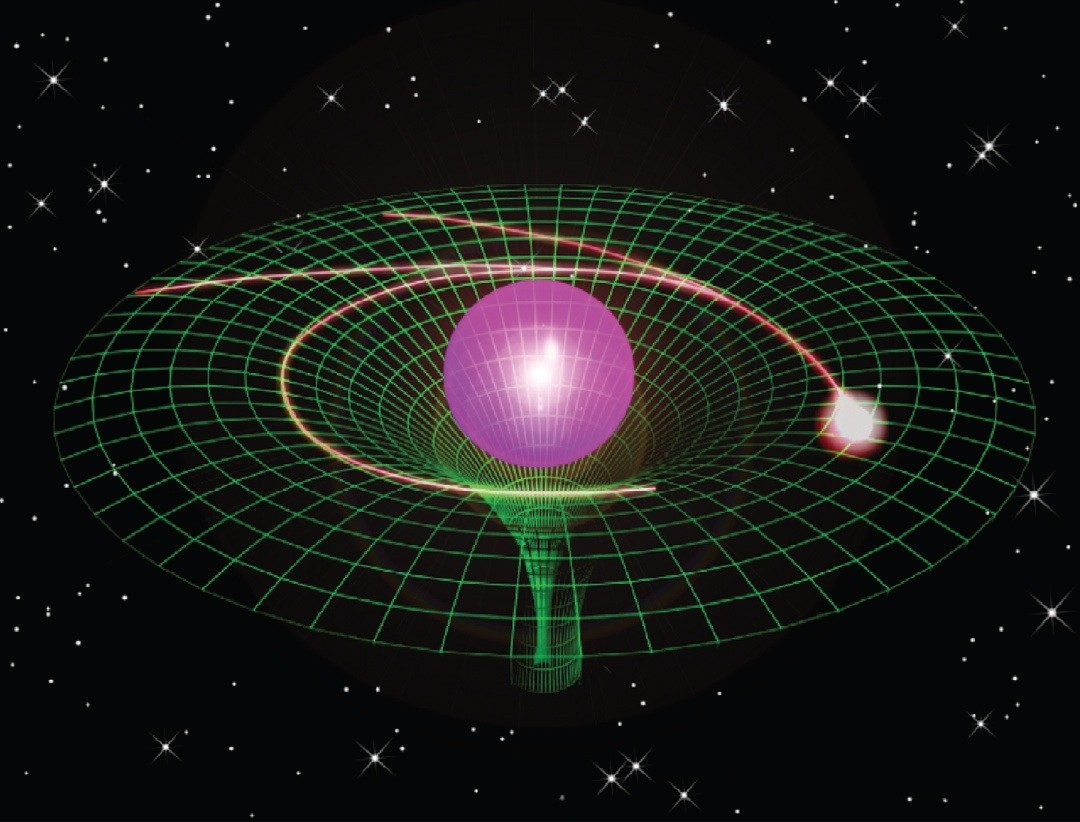

Gravitational Waves are a prediction of Einstein’s General Relativity (i.e, his theory of gravitation). GR stitches together space and time into a single fabric called spacetime. Unlike Newtonian physics where spacetime is a passive canvas on which the dynamics of the Universe plays itself out, GR asserts that spacetime is in fact an active participant. Agglomerations of matter and energy warp and curve the fabric of spacetime, and the geometry of spacetime determines the trajectory of objects in the vicinity of these agglomerations.

If that is not amazing enough, GR further predicts that spacetime can also “ripple”. When massive objects accelerate, they produce these ripples in spacetime that we call gravitational-waves (GWs). They are, however, extremely weak, and therefore notoriously difficult to detect. For example, binary black holes orbiting their mutual centre of mass produce GWs.

These GWs travel billions of light years (the exact distance depends on the location of the source) before they reach the Earth. Their effect on a kilometer long object is to stretch and squeeze it by an amount that’s smaller than the radius of the nucleus of an atom!

Detecting GWs is therefore a monumental challenge.

Nevertheless, the LIGO-Virgo network of ground-based interferometric detectors observed the merger of two black holes in September 2015 (GW150914). A new window to the Universe was thus opened, and a new branch of Astronomy was born, viz., GW-Astronomy.

The vast majority of the GW events detected so far (as of May 2022) have been binary black hole mergers, although merging binary neutron stars and neutron star black hole binaries have also been observed. In fact, arguably the most spectacular detection so far occurred in August 2017 (GW170817), when the merger of a binary neutron star produced both GWs and light (Electromagnetic Waves across a range of frequencies). LIGO-Virgo detected the GWs, and announced this detection to astronomers worldwide, who then followed it up with various telescopes. If memory serves, this is the most followed-up astronomical transient event in recorded history.

Other sources of GWs are also predicted, but remain to be observed (as of May 2022), including (but not limited to) a stochastic GW background produced by unresolved compact binary merger events, continous GWs from isolated spinning neutron stars, and bursts of GWs from exploding stars called supernovae.

Gravitational-Wave Data Analysis

Extracting GWs from detector data is a highly non-trivial exercise. GWs manifest themselves as strains, change in length divided by length, of extended objects. These strains are minute, smaller than one part in a thousand million trillion. Such minute strains are notoriously difficult to measure, even for extended 4 Km long arms in interferometric detectors. Not surprisingly, the GW strain is buried deep in the noise of the detectors. There are many sources of noise, including seismic noise, thermal noise, photon shot noise, etc. Nevertheless, sophisticated data analysis techniques exist to extract the GW from the noise. These techniques essentially use a filtering process that involves cross-correlating the detector data with a theoretical template of the GW. This specific kind of filtering process is called Matched Filtering. Matched filtering can be shown to be the optimal method if the noise is well modelled as a stationary Gaussian random process, and if the signal buried in the noise is well modelled by the template used for matched filtering.

GW signals carry with them imprints of the sources that produced them. Thus, the masses and spins of a compact binary that inspirals and merges governs the shape of the GW.

Since these parameters are not known a-priori, it is not clear which GW template should be constructed for filtering the data. To mitigate this, a template bank is constructed, consisting of hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of GW templates, covering a targeted space of masses and spins. All these templates are cross-correlated with the detector data, and a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) statistic is constructed. The template that provides the largest SNR is expected to be the template that best matches the signal in the data, at least for stationary Gaussian noise.

My Research

Text to appear soon. For now, please click on the Publications tab on the top right corner of this page to check out my publications.